“The pragmatic method is primarily a method of settling metaphysical disputes that otherwise might be interminable. Is the world one or many?—fated or free?—material or spiritual?—here are notions either of which may or may not hold good of the world; and disputes over such notions are unending. The pragmatic method in such cases is to try to interpret each notion by tracing its respective practical consequences. What difference would it practically make to anyone if this notion rather than that notion were true? If no practical difference whatever can be traced, then the alternatives mean practically the same thing, and all dispute is idle. Whenever a dispute is serious, we ought to be able to show some practical difference that must follow from one side or the other's being right.” -William James

“Philosophy recovers itself when it ceases to be the device for dealing with the problems of philosophers and becomes the method, cultivated by philosophers, for dealing with the problems of men.” - John Dewey

Introduction

The “Metaphysical Club” was the semi-ironic name philosopher Charles Sanders Peirce gave to a group of rising intellectuals in Cambridge, Massachusetts, during the late nineteenth century. The name was apt—this motley crew of thinkers, which included Peirce and other first-rate philosophers like William James and John Dewey, engaged in passionate debates about the important intellectual issues of that period. The philosophical school of Pragmatism was born out of these heated discussions. Among its primary sources of inspiration, we count evolutionary science, Puritanism, transcendentalism, idealism, and, last but not least, empiricism. Pragmatism is a radical break with philosophy - an antiphilosophy seeking to go beyond abstract solutions to typical philosophical issues. Pragmatists are distinguished in centering on human agency - action, habit, practice, etc. They try to dissolve traditional problems by testing them against practice. This actionable core of pragmatic philosophy is best captured in Peirce’s famous pragmatic maxim:

“Consider what effects, that might conceivably have practical bearings, we conceive the object of our conception to have. Then, our conception of these effects is the whole of our conception of the object.”

The effects that Peirce is saying define an object are 'sensible' effects, i.e., those that are intelligible and verifiable by human senses. Take a diamond, for example. Our conception of the hardness of a diamond is based entirely on the sensible effects of scratching the diamond. Scratching the diamond is the practice that determines how hard the diamond is. Peirce felt that such a standard clarified long-debated ideas on what makes a scientific hypothesis true.

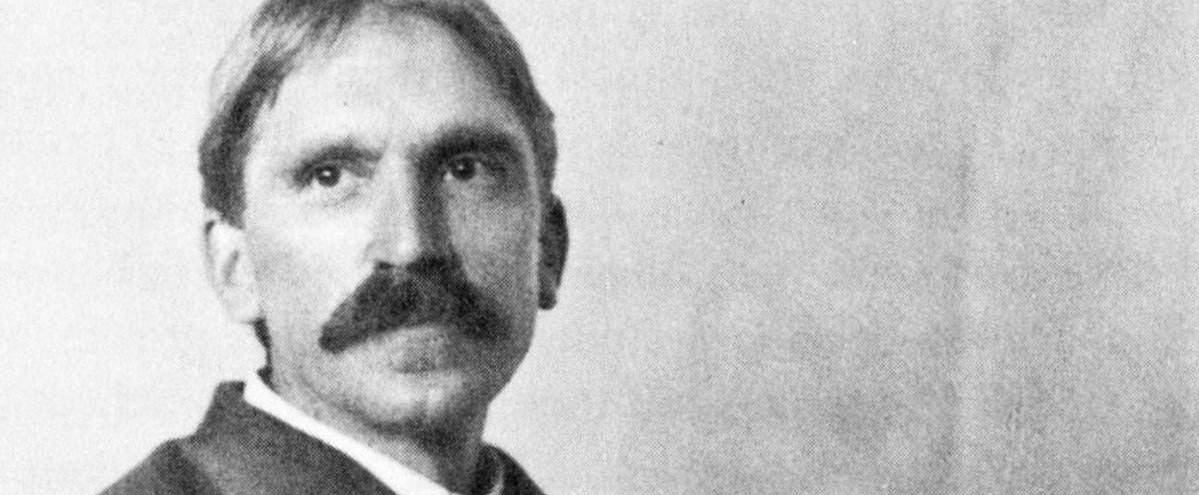

Chauncey Wright

Chauncey Wright (1830-1879) stood out from the other founders of pragmatism. He was significantly older than his peers (nine years Peirce’s senior) and did not have an upper-class academic upbringing like many others. Wright also never committed his thinking to paper. While John Dewey wrote large volumes, Wright developed his thinking primarily through casual conversation. Here is how Peirce described him:

“Chauncey Wright, something of a philosophical celebrity in those days, was never absent from our meetings. I was about to call him our corypheus; but he will better be described as our boxingmaster whom we -- I particularly -- used to face to be severely pummelled.”

Wright had a growing reputation even beyond Cambridge. He corresponded with Charles Darwin, whom Wright impressed with his brief writings on plants. He was also a very skilled “computer” (an old term for someone paid to do mathematical calculations) who could condense an entire year’s work for the National Almanac into a week. During the rest of the year, Wright was having deep philosophical conversations.

Wright’s early proto-pragmatism takes the form of a philosophy of science. For Wright, it was important to distinguish belief from knowledge. The sources of a belief could be anything, but legitimate knowledge could only come from direct sense perception. He felt that any philosophy depending on reason or spiritualism required accepting some presupposition to be valid or even ignoring actual human experience altogether.

Wright's primary target was the contemporary religion-inspired metaphysicians like absolute idealist Josiah Royce. For this reason, his critique of metaphysics started as a critique of religious thinking. Even though he was against religious thinking, he was more concerned with the effects of taking on a belief and less about whether religion was true. His question was: what makes metaphysics desirable as a belief system?

Charles Sanders Peirce

Charles Sanders Peirce (1839-1914) is widely considered the father of pragmatism, which is ironic for two reasons. Firstly, his work outside of pragmatism is downright staggering - he contributed to the theory of signs, logic, the philosophy of math, science, and metaphysics, not to mention his commentaries on various topics like economics and social science. He had hundreds of published writings and almost twice as many unpublished manuscripts. Secondly, Peirce rejected the label ‘pragmatism.’ He dubbed his thought “pragmaticism,” hoping the grotesqueness of the name would be enough to ward off any “kidnappers” of the idea - other philosophers who he felt misunderstood and corrupted his thought.

Peirce starts by analyzing the concept of belief and doubt. In his essay The Fixation of Belief, he says that doubt arises in everyday experience. Belief is the end of doubt. However, he also thought of belief as always temporary. Eventually, doubt sets in, and new beliefs must replace old ones. In Peirce's view, this process of ending doubt is the purpose of thought and reason. From here, Peirce outlines four methods for ending doubt and arriving at belief - 1) the method of tenacity, 2) the method of authority, 3) the a priori method, and 4) the scientific method. The method of tenacity is pure willpower - a belief is true because the believer ardently refuses to consider any other viewpoint, essentially sticking their head in the sand. The method of authority arrives at belief through the force of some institution - the state, a church, civil society, etc. both mandates and justifies the belief. The a priori method arrives at belief through the internal logic of the believer's abstract rational system - this is the belief method of metaphysicians and systematic/technical philosophers. The scientific method arrives at belief by applying the namesake method to the doubtful situation - formulating a hypothesis, rigorous experimentation to test that hypothesis, and analyzing the results of that experimentation to conclude a new belief. As should be of little surprise, Peirce considers the scientific method superior at arriving at accurate beliefs over the other three. According to Peirce, the best method is the scientific method.

Peirce was also concerned with the distinction between meaning and truth. His pragmatism is a theory of meaning, not truth. His goal with pragmatism was to clarify the meaning of concepts, whether metaphysical, musical, anthropological, etc. Peirce sought a meaning criteria by which we could always render our concepts clear, regardless of context. Like Wright, he also wished to dispense with unclear metaphysical problems, which, by their obscurity, follow arbitrary or unjustified criteria that render abstract statements and priori-derived conclusions meaningless. To Peirce, such meaning can only be derived from the practical consequences of accepting a concept. If the belief or lack of belief in a concept makes no discernible difference in how an observer understands and relates to the world, then that concept is meaningless and arbitrary. Hence, the pragmatic maxim I cited in the introduction to this article: for Peirce, the standard for clarification is found in our habits - “Consider what effects, that might conceivably have practical bearings, we conceive the object of our conception to have. Then, our conception of these effects is the whole of our conception of the object.” To illustrate this, he provides an example of the ritual of the Eucharist in Catholicism. During a special prayer, bread becomes the literal body of Christ, and wine becomes his actual blood. However, as Peirce points out, both the believing Catholic and the non-believing observer of the ritual behave the same regardless of their belief - they eat the bread and drink the wine as though it was merely food and drink - and no charges of cannibalism are made during the Eucharist. In other words, the belief or lack of belief in the Eucharist leads to no change in a person’s habits. This renders the transformation of bread and wine into the body and blood of Christ a meaningless belief, in Peirce’s eyes, because it leads to no real change in habit and, thus, no practical consequences.

Peirce proposed two types of truth: transcendental and complex. Transcendental truth is the object of scientific investigation - the transcendental viewpoint asks how things are independent of the language, method, or subjectivity of the person observing them, language, method, etc. Transcendental truth is objective and associated with information acquired from the external world. On the other hand, complex truth is truth that is contingent on the fulfillment of specific criteria. Ethical truths, for example, are complex because the veracity of an ethical proposition depends on a subject’s particular moral stance. Religious truths are also of this type since the rules and norms of a specific religious belief system verify them. The common quality of complex truths is that they cannot be verified by the scientific method.

Representationalism and the correspondence theory of truth are philosophical tendencies that, in brief, view concepts in the mind as reflecting how the external world actually is. In other words, they argue that the function of philosophy is to mirror reality. Representationalism comes from another philosophical tendency that explicitly targets Peirce, Cartesian dualism. Cartesian dualism views the mind and material reality as separate substances. Our mind takes ‘pictures’ of the external world, our sense impressions. Here, we see the tendency of the pragmatists to attack the metaphysical presuppositions mentioned earlier. While the idea that the mind mirrors reality is reasonable, Peirce argues that it is still an a priori presupposition subject to all the typical criticisms the pragmatists launch against assumptions of that type. For Peirce, any concept or belief is true without the “mind representations” of Cartesian dualism. So, the object of a true proposition is something real, and the proposition is true to the extent that it reflects our best, agreed-upon understanding of that real object. And so, a belief (proposition) is true if it would be the final result of some hypothetical scientific inquiry. He introduces a “community of inquirers” to further clarify this standard. This community would converge on the belief itself if it inquired on the matter up to a reasonable point. This is to avoid the issue of a so-called “infinite” limit of inquiry. It also avoids the problem of personal satisfaction being truth since it isn’t the conclusion reached by any arbitrary individual.

William James

William James (1842-1910) was an American philosopher who was part of the Metaphysical Club and is considered the father of American psychology, along with his work in pragmatism. His popularity, both during his own life and after his death, overshadowed Peirce’s. Due to his celebrity status, James articulated his interpretation of pragmatism in a series of hallmark lectures titled “Pragmatism: A New Name for Some Old Ways of Thinking.” These lectures were based on the pragmatic philosophy of Peirce. Before understanding how James interpreted (or distorted, depending on who you ask) Peirce’s pragmatism, it is crucial to examine what he called “radical empiricism” and his views on psychology.

James called his philosophical outlook radical empiricism. He understood empiricism as the viewpoint that accepted or rejected hypotheses based on experience rather than dealing with hypotheses open to revision based on future experience. He put forward three ideas that form the embryo of his approach to understanding the world: possible further thinking about the world: that 1) the only genuine philosophical problems are those which their effect on experience can judge, 2) the relations between things in the external world are as real as the things themselves, 3) the world itself is a continuous flux. Radical empiricism, understood as these three elements together, is as radical as it is strange and, on the surface, totally unintuitive. However, James understood these three ideas as comprising a unique approach to philosophical monism (the idea that the world is one, that there is only one fundamental “thing” in the universe) that broke with traditional ways of understanding monism. He sees the world as a unity of relationships - a giant web that links everything to every other thing because they all interact. Ironically, radical empiricism is a starting point but not a foundation. It initiates James’ philosophical exploration of the world, but it is yet another hypothesis that needs to be inquired about. We can go back and challenge any of James’ three points of radical empiricism, or we can take them for granted and continue inquiry with those points as axioms.

James’ version of pragmatism aligns with and diverges with Peirce. It is best to start with his interpretation of the pragmatic maxim, given during his famous lectures on pragmatism:

“The ultimate test for us of what a truth means is indeed the conduct it dictates or inspires. But it inspires that conduct because it first foretells some particular turn to our experience which shall call for just that conduct from us. And I should prefer […] to express Peirce’s principle by saying that the effective meaning of any philosophic proposition can always be brought down to some particular consequence, in our future practical experience, whether active or passive; the point lying rather in the fact that the experience must be particular, than in the fact that it must be active.”

Both James and Peirce view pragmatism as clarifying certain muddied concepts in philosophy by emphasizing the need for practical differences to decide whether we accept or reject them. However, James distinguishes his pragmatism from Peirce’s in two key ways. Firstly, he emphasizes the sensible effects of the truth on the individual, as Peirce is far less concerned with the experience of individuals. We could attribute this emphasis to James’ empiricist roots, which center on psychology and individual experience.

Secondly, while James agrees that pragmatism is a theory of meaning, he also adds that it is a theory of truth. For him, Truth is not an objective quality that real things ‘possess’ but rather a property of our beliefs. The external world cannot be true or false. It only ‘is.’ It is our beliefs about the world that can be true or false. This means that James is a philosopher of correspondence - in his eyes, truth is a relation between a belief and reality. To practically test this relation, James introduces the concept of a plan of action. Without such a plan, we could not reach any of the practical consequences that pragmatism claims constitute our standard of truth. Thus, successfully carrying out this action plan is the verification process that affirms a belief. The truth of a belief is to be identified with such a process.

James was also the first lecturer of psychology to offer a course in the United States and wrote the highly influential Principles of Psychology. There are two important philosophical ideas in James’ approach to psychology. First, James argues that we should treat psychological phenomena as empirical. He says that we can learn whatever it is possible to know about the human mind through empirical inquiry. In contrast to past empirical thinkers, James emphasized that consciousness cannot be understood as a series of discrete and distinguishable experiences but that experiences blend to form a single, constantly fluctuating ‘stream’ of consciousness. For James, the continuity of the mental world parallels the continuity of things and their relations in the external world, too.

Note the need for community or inquiry in James' pragmatism. James is comfortable with individual satisfaction being the standard for truth since that is how people experience beliefs. However, ‘individualizing’ objective truth has apparent flaws. Sometimes, James tries to correct this—he calls a true belief a belief in something expedient “in the long run and on the whole.” This definition tries to transcend the individual element of James’s pragmatism. Despite this noble attempt, James’ concept of belief undermines the endeavor. In his 1896 essay “The Will to Believe,” he extends the idea of evidence to articulate his views on belief. Evidence is not merely objects which verify an idea scientifically (or pragmatically). James argues that evidence has to include intimate personal experiences, and he applies this criterion most strongly to the existence of God. It is rational to believe in God if the power of religious experiences makes such a belief evident in the subject. James himself is a theist for these very reasons.

By focusing on the consequences of a belief in practical conduct, James proposes that beliefs can be justified by those consequences rather than evidence or logic. For example, a consistent belief in God demands certain moral conduct that an atheist cannot justify taking part in—and so a belief in God does not require evidence but a change in conduct. A more mundane example is a “belief of confidence.” A pilot who has to emergency land a plane in the middle of the Hudson River has to believe that she can do so confidently to save her passengers. Whether this is true or not is irrelevant: James is only asking whether or not holding that belief would lead to real consequences in how we act. And if those real consequences exist, then a belief is justified on those grounds alone. By shifting justification from evidence to practical consequences, James' satisfaction criterion and radical extension of evidence transform the typical idea of what it means to believe.

From James's point forward, the whole history of pragmatism can be categorized by a split between the ‘Peircian’ and ‘Jamesian’ traditions. The former tendency is best represented in the analytic and linguistic circles of the twentieth century - it restricts pragmatism to a pure theory of meaning and clarity that seeks to incorporate scientific rigor into the problems of philosophy. The latter tendency is best represented in the works of John Dewey and, later, Richard Rorty—it opens pragmatism to a theory of truth that often has controversial results.

John Dewey

John Dewey (1859-1952) is arguably the most influential American philosopher ever. He lived for 92 years. At 27, he published his first book (Psychology); at 90, he published his last (Knowing and the Known). He wrote sixty volumes of essays within those 63 years as a philosopher—almost an entire volume of text a year! Dewey wrote about nearly every topic, tackling many significant philosophical and political problems.

Like William James, John Dewey also took on a form of empiricism called ‘naturalist empiricism.’ For Dewey, thought is the most developed way for an organism to relate to its environment. Drawing from Darwin, Dewey presents thought as a product of evolution. In the sense that it is a biological process, it is no different than homeostasis. Dewey posits this view of thought to reject the subject-object split in philosophy in the spirit of Peirce’s anti-Cartesianism.

Dewey argues that experience can’t be divided into the extremes of an experiencing subject and an inert “object” to be experienced. Instead, as Dewey puts it, knowledge, or the “object of knowledge,” is constructed by thought. Dewey rejects the “spectator theory of knowledge”—that knowing has no bearing on the object to be known. Instead, he claims that the object of knowledge is donned with traits that it did not possess previously but that this donning isn’t something passively “thrown onto” the object. This is an admittedly strange viewpoint and a bit hard to grasp. A metaphor to help illustrate this can be understood through sculpting. The marble is the ‘object of knowledge’ outside the mind as an objective and independent entity. The sculptor, however, by placing himself in relation to the marble, modifies it with additional traits and relations. The act of sculpting a statue, which we can call the act of knowing, and the whole relation between the sculptor, the sculpting, and the marble is a totality where each part plays a role in constructing the final whole. James felt that the traditional understanding of knowledge where the subject is purely an external 'spectator' incorrectly posited that the object of knowledge, the marble, was unaffected by the knowing or the sculpting. This would mean that knowing and the object of knowledge do not relate. However, by placing the knower and the act of knowing together in an organic unity, Dewey can bridge the gap between subject and object and form a deeper understanding of the role of subjectivity in knowledge.

Next, Dewey’s concept of inquiry starts with the conception of thought being seen as an interruption of the habitual reactions that organisms have to their external environment when that environment poses issues to the organism that require some reflection to solve. In other words, the environment poses what he terms a problematic situation to the organism that it is forced to overcome for whatever reason (for example, an organism needs to find a new source of food after a drought). In this case, unconscious, reactive responses will not do. Inquiry is, therefore, the process of thought by which the organism “reconstructs” the conditions of the problematic situation in the mind and, after struggling with it intellectually, forms a possible plan of action to resolve the situation. The scientific method is simply a more sophisticated version of this process. Conversely, inquiry, which seeks to overcome a problematic situation in everyday life, uses this crude version of the scientific method.

Various ‘humanisms’ - human interests, values, psychological states, ethics, values, cultures, histories, narratives, etc.- mediate how the subject experiences the world. This insight guides Dewey’s attitude toward logic. Again, inquiry is driven by biology. Our conceptions of truth and reality depend on our development as living organisms. For the traditional logicians, logic is concerned with correct reasoning. For Dewey, however, the fact that logic is a natural function rather than a transcendental structure of knowledge means he displaces the role of traditional logic with their function in human practices. Logicians treat the study of the structure of things like symbolic statements as if they stood independent of real human practice. For Dewey, this transcendence is an unwarranted assumption. Since logic is instrumental to human experience, it cannot be divorced from it in philosophy. For Dewey, this revaluation of logic is a reconstruction that sets about his philosophical project in various other domains.

Since the organism and its environment are meshed, any problematic situation a subject is forced to grapple with is characterized by doubt. For Dewey, doubt, oddly enough, is a quality of a situation rather than of an inquirer or belief. As mentioned, any object of knowledge for him is constructed by inquiry—it does not precede the inquiry process.

For Dewey, the end goal of ethics is intelligent conduct. Ethical acts must occur within habitual actions—actions that precede conscious thought. For example, take something as simple as walking. For Dewey, an ethical inquiry would mean asking what the 'correct posture' is while walking. In this case, intelligent conduct would suggest keeping your back straight and not hunching. An ethical inquiry would involve applying intelligence to habits in a similar way. Inquiry applied to ethics here reflects Dewey’s commitment to using the scientific method in all forms of life, for he sees no gulf between science and ethics. The only factor distinguishing science from ethics is that human conduct is the end goal of ethical inquiry, not scientific inquiry. Conduct is a way of being, not necessarily a series of moral facts to be applied to ethical dilemmas as formulas. Since the ‘way of being’ is quite vague as the end result of the inquiry, Dewey employs an idea of social progress as the basis for this inquiry. Human conduct improves our society, and this conduct is a result of proper ethical inquiry.

This all plays into Dewey’s naturalism from earlier times—ethics do not come from eternal norms but are constituted by social relations. Morality, for example, is acquired by the social subject via their position in this social web.

Only through inquiry can we reconstruct experience to overcome a problematic moral situation. For Dewey, growth is the only end of ethical inquiry since growth implies a perpetual positioning of oneself in a way that leads to further moral inquiry—in the same way that a belief is a hypothesis meant for future investigations. For those who know mathematics, this is a bit like a recurrence relation, where inquiry begins on a belief and leads to a belief that is, once again, subject to inquiry.

Our relations with others make us social beings—our being is “stamped” with the mark of our community. Again, Dewey’s primary concern is growth and development—in modern society, institutions should be structured in a way that reproduces and expands social growth. What ‘growth’ means here is democratic progress. There is a paradox here—social beings are determined by existing society, but these very same determined social beings change society, thus determining it. How can social beings ever alter society? Dewey’s answer rejects this paradox as relying on a static relationship of determination. It goes against the organic unity between the organism and its environment. He seeks to reject concepts that delineate the nature of institutions like the State that would ‘staticize’ those institutions. Such abstractions applied to social institutions do not allow them to be subject to inquiry and, thus, subject to growth.

Dewey’s standard for supporting or changing a social institution is how it affects the growth of individuals in society. He endorses democracy as the political institution that best fulfills his growth requirement. Dewey argues that the democratic attitude best supports inquiry as it manifests in various fields, including the sciences, law, and education. For Dewey, these fields already engage in the inquiry process to develop their concepts. When that inquiry is democratic, all are free to engage—to hypothesize and criticize others—in an open investigation into problematic situations. Only when inquiry is in this liberated form can the community develop and accept shared social values. Any other system only impedes this process. Values only represent a community if they result from democratic inquiry. Democracy also affirms Dewey's attitude toward experimentalism. The democratic political order always asks what makes the most egalitarian society, which would require an open mind to endless social experimentation. This is because, as time passes and society develops, our external environment will continue to pose different problematic situations requiring creative and novel solutions.

Pragmatic Marxism

On the surface, pragmatism and Marxism have a superficial relationship. They are only comparable because they are philosophies centered on a vague notion of action. Marxism centers action through the concept of praxis, which Marx defines as sensuous human activity in his Theses On Feuerbach. This definition has profound implications since Marx uses it to encapsulate many philosophical ideas (the sensation of idealism, the ‘thing-in-itself,’ human nature, etc.). However, his conception of human action is the most important thing in Marx's theory of praxis.

In the classical sense (within the works of Peirce, James, and Dewey), pragmatism centers action in a very general fashion. Action is simply defined as human practice. This is what we termed human ‘agency’ earlier—behavior, habits, etc. The difference is that it lacks all the profound philosophical implications that action conceived as praxis has in Marx’s philosophy. Instead, as the classical pragmatists understand it, practice is much closer to our everyday understanding of simply being things we do. Marx’s praxis contains this simple, common-sense notion but goes far beyond its scope. Even though Marx’s praxis contains pragmatic practice, if we ventured under the surface, deeper into both tendencies, we would find that they diverge pretty quickly.

Pragmatism and Marxism are, superficially speaking, incompatible. A fundamental emphasis on class characterizes Marxism. In Marxist philosophy, class colors everything. It is the most defining feature of the theory. Non-Marxist philosophers can utilize Marxism, as they can imbue everything with class analysis. However, Marxism is a tool for the social and historical investigation of communists and socialists. It is meant to be the theoretical framework to interpret and change the world, as is famously expressed in Marx’s often repeated Eleventh Thesis on Feuerbach - “The philosophers have only interpreted the world in various ways; the point, however, is to change it.” The same cannot be said for pragmatism.

Pragmatism lacks this class character, which bleeds throughout all Marxist inquiry. It doesn’t have any revolutionary social intent, so to speak. As a philosophical movement, pragmatism isn’t seeking to change the world in one way or another, and certainly not for a communist future. Pragmatism is a methodological paradigm that doesn’t inherently admit any desire for a future state of society. Because of this lack of class analysis and social intent, the Marxist perspective would describe pragmatism as a ‘bourgeois’ philosophy. Without a class perspective, pragmatic thought cannot achieve social revolution, nor will it bother trying. It is just another politically inert thought that does not get at the heart of social change. Although the tradition of pragmatism is rife with political perspectives and desires (the liberalism of thinkers like John Dewey, William James, and, more recently, Richard Rorty are the best examples), communist revolution, or any revolution for that matter, is not an essential concern of pragmatism. These immediate observations would render pragmatism incompatible with Marxism, which has been historically argued by Marxists and pragmatists alike.

Despite the superficial relationship and incompatibility between pragmatism and Marxism, bridging the two philosophies is a fruitful endeavor. We have to remember that the connection (or lack of connection) between philosophies is not an ‘objective’ fact. The incompatibility of pragmatism and Marxism is not set in stone. There is no final word on the relationship between pragmatism and Marxism because there is no final word on anything in philosophy. Philosophy is characterized by endless interpretation. None of its arguments or tendencies are ever really ‘settled.’ We often think the hard sciences operate in this permanent manner; after all, 2 + 2 will never be 5. Even though this isn’t “set in stone,” it is considered much closer to being settled than the objects of philosophical debate. Philosophy is arguably considered the softest science and has the least agreed-upon standard of what ends the debate. This means we’re free to go ‘backward’ in philosophy at any time without risking being considered archaic or seen as rehashing long-settled debates. We can ‘go back’ and rethink whether there is a lack of compatibility between pragmatism and Marxism. We can try our best to revive the topic and envision a new pragmatic Marxism. The reasons why we should bridge these two philosophies will be presented below. But first, it is appropriate to touch on an attempt to already do so in the history of philosophy. We will briefly explore the most apparent historical effort at bridging the philosophies of pragmatism and Marxism—in the early work of Sidney Hook.

Sidney Hook (1902 - 1989) was an American philosopher and public intellectual. As a teenager, he was a communist, supporting the early Socialist Party of America during its heyday under the famous socialist politician Eugene Debs. Hook studied under John Dewey during his doctorate program at Columbia University. This undoubtedly influenced his pragmatic leanings. He remained a Marxist throughout the 1920s and 1930s; however, in the 1940s and beyond, he began to criticize Marxism, specifically what he viewed as authoritarianism in Marxism-Leninism and the Soviet Union. After the 1950s and 1960s, he became a full-blown McCarthy-style anti-communist, arguing in favor of the removal of professor Angela Davis from UCLA on the grounds of her communist beliefs. He died as a member of the conservative Hoover Institution in Stanford, California.

We are not interested in Hook's anti-communist pivot but in his early bridging of Marxism and pragmatism. He grounded this connection by accepting the pragmatic theory of knowledge and truth and applying it to Marxism. This theory contrasted two other theories of knowledge: 1) the correspondence theory and 2) the coherence theory. As a reminder, the correspondence theory of knowledge understands true knowledge as knowledge that accurately “mirrored” or “copied” phenomena in the external world, the mirror itself existing in the mind of a “spectator.” Coherence theory takes true knowledge as consistency within an entire web of beliefs. Under this view, we determine whether a new belief is true or false by the degree to which it comfortably fits with the rest of the knowledge we already possess about the world. The pragmatic theory of knowledge sought to reject these two tendencies by positing that knowledge is fundamentally instrumental. Like with Dewey and against correspondence, true knowledge is not an inert picture in the mind. Against the coherency theory, true knowledge could not be coherent in a “web of beliefs” since such coherence is based on established beliefs - which pragmatists felt were like axioms. Only purely abstract systems, like mathematics, can have this characteristic. There are no fundamental axioms regarding the truth of empirical observations.

According to the pragmatic theory of knowledge, knowledge is true because it helps humans predict and control aspects of their external environment. Hook borrowed this pragmatic theory from Dewey. He felt that this instrumental concept of truth centers on humans' active role in establishing truth. Following this, Hook attempted to apply Peircian ‘fallibilism’ to social analysis. Hook interpreted Marx’s Eleventh Thesis on Feuerbach as justifying this instrumental pragmatism. In the Theses, this meant that Marx’s exhortation to “change the world” was not only a demand to act but a call for us to understand the inseparable nature of thought and practice. Hook connected pragmatism to Marxism by arguing that truth is an instrument meant to transform the social conditions of man. Truth isn’t a ‘mirror’ to be discovered passively by philosophers; instead, it is the evolving set of beliefs we use to navigate and transform the world around us.

Hook also attempted to apply Dewey’s experimentalism to Marx’s theory of history. Instead of emphasizing historical inevitability, Hook argued for a conception of Marxism that was testable and verifiable. He accepted wholeheartedly that Marxism is a science applied to history and society. This, again, paralleled pragmatism’s enduring commitment to the scientific method. For Hook, Marxism is the Deweyan resolution to a problematic situation: the contradictions of capitalist society. To be such a solution, Marxism had to be seen as a constantly tested implementable hypothesis rather than an absolute Truth. Marx did not offer axioms in his work but proposed theories that could only be brought to reality through action.

Furthermore, it opened Marxism to the possibility of rejection when its predictions failed to come to fruition. Before his anti-communist pivot, Hook considered Marxism to be faith-based and normative. By the end of his Marxist career, however, Hook had embraced Marxism as an experimental science of history that could be verified by observing the future relationship between the productive forces and the class relations that would appear in a socialist society.

Pragmatism is America’s most prominent contribution to Western philosophy. Culturally speaking, the typical American is viewed as “being pragmatic” in common usage, which means hard-nosed practicality. Think of the “rugged individualism” and “frontier mentality” usually associated with Americans. Even William James uses the term “cash value” to measure the utility of ideas. Given the United States’ long history of capitalism, this further shows how pragmatism is a fundamentally American philosophy.

This does not mean, however, that pragmatism should be rejected. Pragmatism is America’s philosophy, and we should follow in the footsteps of our great communist thinkers in how they treated their national philosophies. Marx engaged in the German Idealist tradition, chiefly through his critique of Hegel and his engagement with other German philosophers like Kant and Feuerbach. Gramsci engaged in the Italian tradition, analyzing the political thought of Niccolo Machiavelli in his most famous writing, The Modern Prince, as well as studying and critiquing the historicism of philosopher Benedetto Croce. Even Lenin follows this tendency, albeit to a lesser extent, when he engages in Russian philosophy in his work Materialism and Empirio-Criticism. In it, he critiques the Neo-Kantianism of Russian philosophers like Bogdanov. All these communist thinkers grappled with the philosophies that arose in their national context. They each considered those philosophies bourgeois, and we, as American communists, should also feel the same way about pragmatism. However, unlike Marx, Gramsci, and Lenin, American communists think that because pragmatism was developed in the context of capitalist America, it offers nothing of value to Marxist theory. They find the tendency is utterly useless since it is not Marxist philosophy proper - it is not dialectical materialism. But this narrow-minded approach limits the resources available to our movement.

Communists must engage in the philosophical tendencies of their nation. This isn’t for any reason outside of basic historical materialism - Communists must engage in the overall history, culture, and other intellectual “spheres” of their nation as well. Without understanding its historical foundations, one cannot hope to change society's trajectory. To connect pragmatism and Marxism is to follow through with this commitment in philosophy.

Pragmatism is a philosophy that, historically speaking, seeks to dissolve philosophical issues that do not make any difference in human practices whatsoever. We see this tendency clearly in William James’s lectures. As stated earlier, James tries to put certain quarrels at rest, such as the belief or lack of faith in God, by emphasizing that taking either side in that debate does not change the practices of the people arguing. Regarding pragmatic Marxism, we must apply this act of dissolving to American communist discourse. However, we do this by modifying James’ original idea. The debates we should put to rest are not to be dissolved based on a change in general human practices; they should be dissolved under the consideration of whether they do or do not change our political practices - the general political activities we participate in as communists. Not all debates can be dissolved this way - plenty of “abstract” conversations make a political difference. For example, whether to support bourgeois candidates in national elections is a debate that cannot be dissolved in this way. However, for instance, whether or not the Great Leap Forward was good or bad for China has zero consequences on the political practices of American Communists. We will all carry out the same activities whether or not we agree or disagree. Yet these types of historical conundrums arise endlessly in communist discourse. Beyond the particular debates, it is crucial to discern between genuine, practical ideological rifts and pure scholastic noise. Scholars of Chinese history need an answer to the discussion on Mao’s policies. The same is not true for the American communists.

Niccolo Machiavelli was not a pragmatist because his life predates the birth of pragmatism by roughly four centuries. Nonetheless, his most famous political insight, that the ends justify the means is a starting point for a pragmatic understanding of political ethics. Machiavelli was much more complicated and subtle in the derivation and usage of this phrase. Still, for the sake of this essay, we will instead use the basic idea as the foundation for a pragmatic view of politics and ethics. A deeper understanding of Machiavelli is discussed in other works in this publication.

What is ethical for the political revolutionary does not lie in adhering to abstract principles. What is moral is whatever works - in this case, it is whatever helps communists expand their movement, whatever brings communism to actual political events where our participation means spreading our influence. Ethical principles and political revolution have a complicated relationship. We are communists, so we are moralistic to a large degree, a degree necessarily larger than capitalists. But we also have a world to win. Although everyone claims to be “pragmatic” (in everyday usage of the phrase) when it comes to doing the “dirty work” of politics, communists fail to do so consistently. There are legitimate political pragmatists; however, few communists qualify as these shrewd politicians. We hold on to our moral principles for dear life in the hopes that, in this death grip, we remain authentic communists—legitimate members of our tiny sect.

Because communism has no real base in America, abandonment of such principles appears as conceding the little ground that we hold. However, principled communism often amounts to practical abstention from political practices necessary for its growth as a movement. We hold such small ground for the very reason that we are unwilling to have a political practice that either goes against or beyond our principles. We engage with members of trade unions but not with veterans because unions are where the morally pure worker is, but not veterans because veterans are former imperialist foot soldiers. We participate in mutual aid for the homeless because we have ethical principles to look out for the poor and downtrodden. At the same time, we abstain from city council meetings where policies that directly affect them are voted on because such meetings are mere liberal politics. We are so above real politics that all we tend to do is fall below it.

Enjoy the article? Support us on Patreon!